MENTAL HEALTH & ADDICTION REHAB CENTER IN MALIBU

Highest Standards, Nationally Recognized:

Luxury Mental Health Facility

Luxury Substance Use Treatment Facility

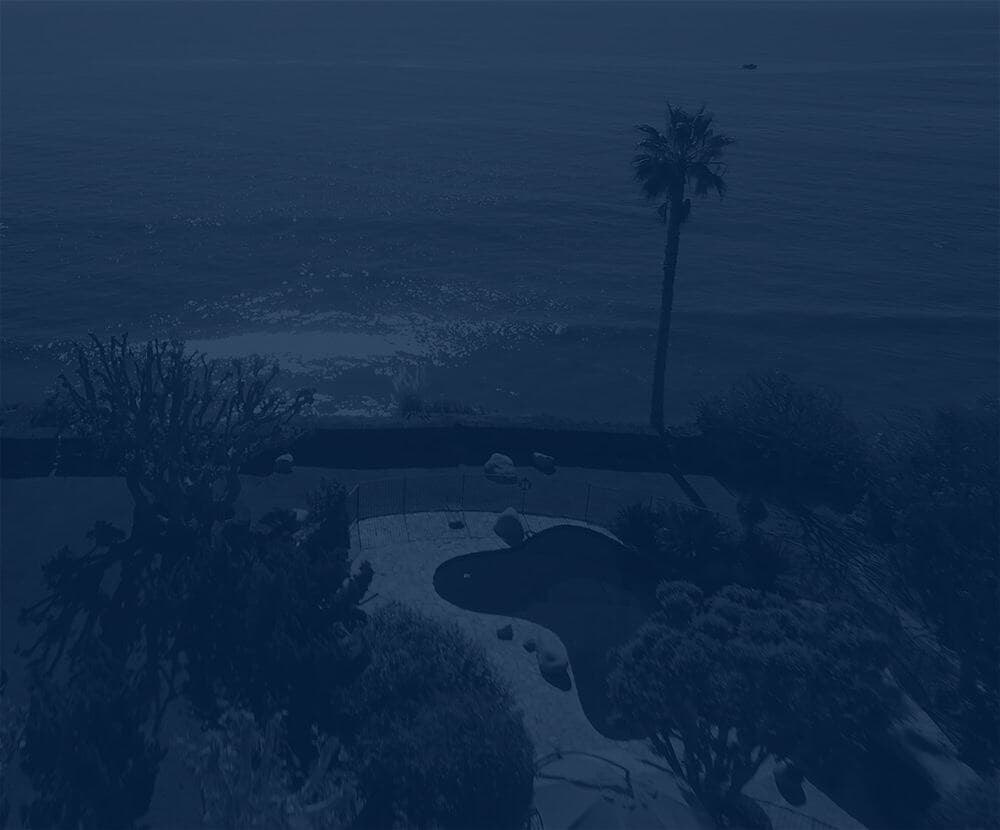

Oceanfront Luxury Addiction and Mental Health Treatment Center

Avalon Malibu is a nationally recognized, dual-licensed treatment center in Malibu, California, specializing in mental health, addiction rehab, and dual diagnosis care.

Our two oceanfront estates offer six private suites each, with direct beach access and serene spaces designed for transformation and peace.

Here, evidence-based therapy meets holistic wellness. Clients receive personalized treatment for mind, body, and spirit, supported by a 6:1 staff-to-client ratio and 24/7 on-site nursing.

Established in 2011, Avalon has served individuals and families for 15 years. Set along the Malibu coast, Avalon provides more than treatment. It’s a sanctuary for renewal, connection, and lasting freedom.

Call us at 1 (888) 958-7511. Our team is ready to help you.

6 to 1

staff to client ratio

24/7

on-site nursing team

1700+

clients and families guided

Mental Health Disorders We Treat

Our highly experienced staff at Avalon Malibu evaluates the needs of each client as they are admitted, conducting a full dual diagnosis assessment for the following mental health disorders:

- Antisocial Personality Disorder

- Anxiety Disorder

- Avoidant Disorder

- Bipolar Disorder

- Borderline Personality Disorder Treatment

- Burnout

- Dependent Disorder

- Depression

- Dual Diagnosis

- Histrionic Personality Disorder

- Mental Health Diversion

- Mood Disorders

- Multiple Personality

- Narcissistic Disorder

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- Panic Disorder

- Paranoid Personality Disorder

- Personality Disorder

- Phobia

- Post-Traumatic Stress

- Process Addiction

- Schizoid Personality Disorder

- Schizotypal Personality Disorder

- Trauma

Substance Abuse Disorders We Treat

We embrace addiction and the concurring mental health aspect of treatment and work on each client’s physical, spiritual, and emotional wellness. Our expansive attention to the following addictions includes:

- Adderall & Prescription Stimulants Addiction

- Alcohol Addiction Treatment in Malibu

- Ambien Addiction

- Barbiturate Addiction

- Benzodiazepine Addiction

- Cocaine Addiction

- Ecstasy MDMA Addiction

- Heroin Addiction

- Marijuana Addiction

- Methamphetamine Addiction

- Opioid Addiction

- OxyContin Addiction

- Valium Addiction

- Xanax Addiction

Malibu’s Most Exclusive Recovery Haven

Our large oceanfront grounds and breathtaking view provide every patient with a vision of clarity and rejuvenation. When our clients step through the doors of our luxury residential rehab center, they feel the realization that change can and will happen here.

We have created the most exclusive addiction and mental health recovery space you will find on the West Coast, and invite you to experience treatment luxuries that are designed to help you in seclusion, privacy, and comfort. Our rehab and mental health center addresses the complex relationship between environment, internal mental health, and the root causes of addictive behaviors and substance use.

Avalon Malibu is a California state licensed luxury residential addiction and mental health treatment center dedicated to the healing of adults experiencing substance abuse disorders as well as psychiatric and mental health issues. We combine world-class clinical care with a deep commitment to lasting personal transformation.

Foundation for a Healthy Lifestyle

We craft the best possible environment to make sure everyone is happy, healthy and comforted. We create a balanced dynamic of clients that interact and support each other throughout their rehabilitation with us.

Our team of experienced mental health and addiction specialists provide the highest level of individualized care from the moment clients walk in, until long after their last session is complete.

Our clients find they can indeed build a strong foundation for a healthy lifestyle devoid of addiction and successfully manage their mental health in the most beneficial ways. We encourage everyone to practice freeing their minds from addiction’s control on their lives and managing mental health.